Hip Dysplasia

What is hip dysplasia?

The word “dysplasia” means “abnormality of development”. Hip Dysplasia is a canine genetic condition in which there is a tendency towards development of hip laxity early in life. Hip dysplasia is not congenital because affected dogs are born with morphologically normal hips. The soft tissues (ligaments and joint capsule) that normally stabilize the hip joint become loose within the first few weeks of life. The consequence of this laxity is that the normally very congruent ‘ball and socket’ hip joint becomes much less congruent. The ball becomes flattened and deformed and the socket becomes more saucer-shaped. All dogs with hip dysplasia develop secondary osteoarthritis of the affected joint. The vast majority of affected dogs have dysplasia of both hips.

What is the cause of hip dysplasia?

This condition is primarily of genetic cause, although environmental factors such as obesity during puppyhood may influence whether an animal with the genes coding for hip dysplasia will develop a clinical problem. Current estimates state that more than one hundred genes code for hip dysplasia. It is important to recognize that environmental factors are unable to cause hip dysplasia, although they can influence whether an animal with the genes that code for hip dysplasia will develop a clinical problem. There is no evidence to support the concept that excessive exercise during puppyhood can contribute to the development of hip dysplasia.

How can I tell if my dog has hip dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia is the commonest orthopedic condition in dogs. It most frequently affects large rapidly growing dogs, although small dogs and cats can also be affected. The onset of clinical signs is variable, but hip dysplasia is most commonly diagnosed between 6 and 12 months of age. The clinical signs are very variable and include stiffness, exercise intolerance, difficulty getting up or lying down, problems climbing stairs, and gait abnormalities, including limping on one or both back legs. It is rare for dogs to demonstrate overt signs of pain at home, although clinically affected dogs are often very painful when their hips are extended by a veterinary surgeon.

What is happening inside an affected joint?

Pain is caused initially by repetitive strain injuries to the lax hip stabilizers, and micro fracturing of the bone and cartilage surfaces that are rubbing past one another. As cartilage erosion progresses, pain is the result of the global joint disease known as osteoarthritis.

How is hip dysplasia diagnosed?

Hip dysplasia is diagnosed, in most cases, following a multimodal evaluation process between you, your primary care vet and a specialist orthopedic surgeon.

In the first instance you may have noticed your dog exhibiting some or all of the following clinical signs;

- Stiffness

- Exercise intolerance

- Difficulty rising, sitting or lying

- Difficulty climbing stairs or getting in and out of the car

- Abnormal gait – Sometimes described as a ‘swaying’ gait during walk

- Limping on one or both hind limbs

- Protective of hip region during grooming or bathing

- Pain – not necessarily in all dogs

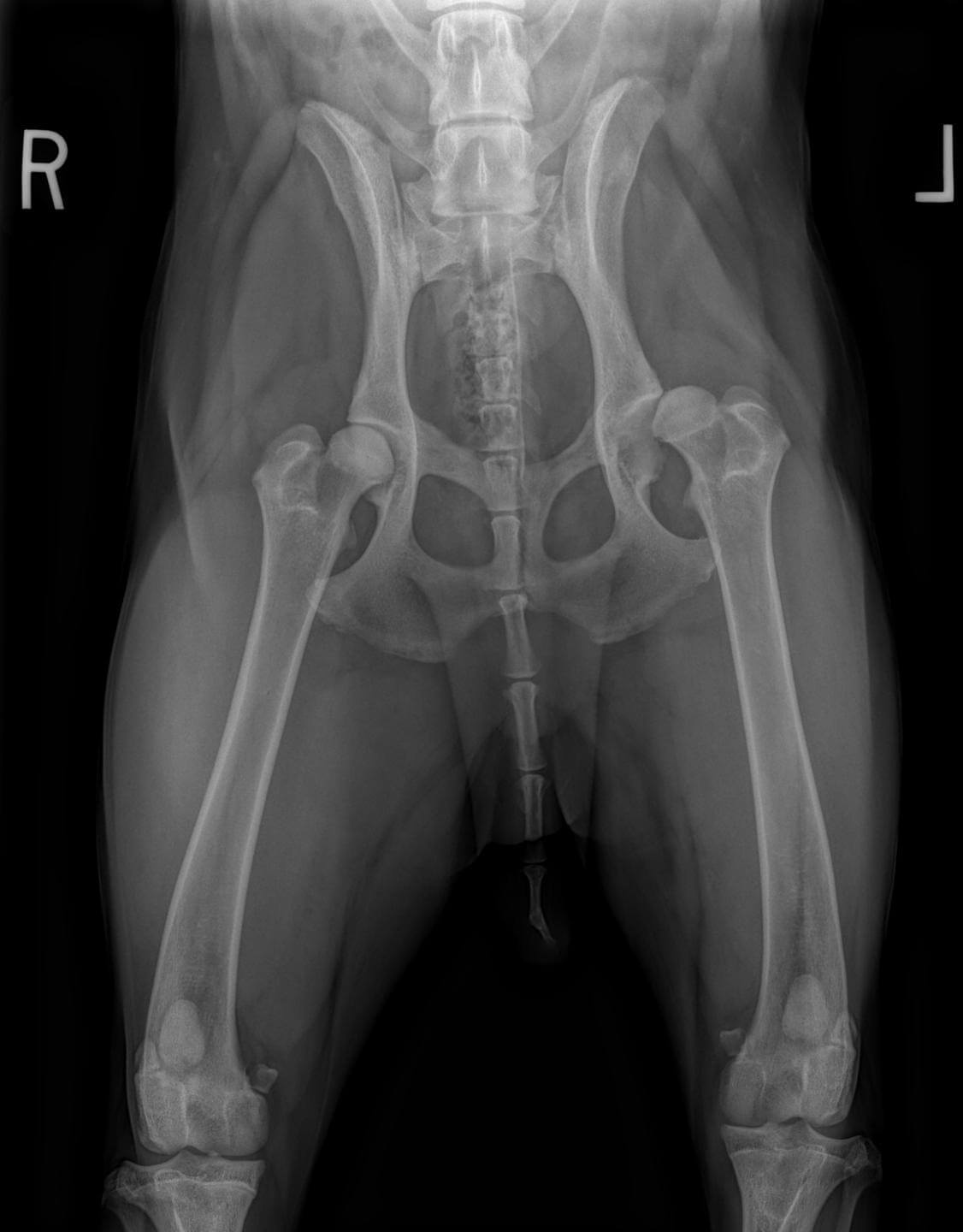

Your primary care vet may have recognized an abnormal gait or noticed hip pain in your dog during routine health checks or following concerns raised by you. If your primary care vet has a suspicion of hip dysplasia, they may perform radiographs of your dog’s hip joints. Radiographs will usually show changes in affected dogs, although this is not always the case. More often than not your dog will be referred to have a consultation with an orthopedic surgeon.

Following referral to Oakdale Veterinary Group, a thorough orthopedic assessment will be performed. During this time, the clinician can advise of a provisional diagnosis and discuss possible courses of action. Depending on decisions made, your dog may be admitted to the hospital to allow radiographs of the hips joints under sedation or general anesthesia. It may also be advised that your dog has additional diagnostic imaging such as CT or MRI which will require for your dog to be referred to a bay area hospital such as UC Davis. Your dog will receive one-to-one nursing care throughout the process by one of our registered technicians who are all highly trained and experienced in anesthesia and sedation.

The orthopedic clinician will also perform a specific manipulative evaluation of your dog’s hips called an ‘Ortolani’ test. This test is performed while your dog is heavily sedated or under general anesthesia and is used to assess laxity in the hip joint.

Following diagnostic imaging and complete clinical examination, your clinician will be able to advise you of the treatment options suitable for your dog.

How is hip dysplasia treated?

The best treatment for hip dysplasia depends on many factors, but the most important is the severity of the clinical problem. In some dogs, the clinical problem is mild, and in some cases, the diagnosis of hip dysplasia was incidental as part of a screening test (e.g. for a dog being considered as a breeding animal). In other dogs, the clinical signs are more obvious and treatments will target not only the current problem but also the potential problems that the individual is likely to face later in life.

Non-surgical management of hip dysplasia

Non-surgical management is recommended in dogs that are diagnosed with hip dysplasia as an incidental finding. For clinically affected dogs, the likelihood of a good response to non-surgical management depends on how severe the hip pain is. The cornerstones of non-surgical treatment are body weight management, physiotherapy, exercise modification, and medication (anti-inflammatory pain killers). In the short term, most dogs will make an improvement when they are managed appropriately. Unfortunately, the improvements are rarely maintained in the long-term. The majority of dogs followed to later life have ongoing exercise restriction and require medications. Nine out of ten dogs have painful hips when assessed by a veterinary surgeon.

Surgical management of hip dysplasia

Surgical treatments are divided into procedures that modify the hip anatomy and procedures that are considered salvage surgeries. To find out more about these procedures please visit the information pages for these techniques:

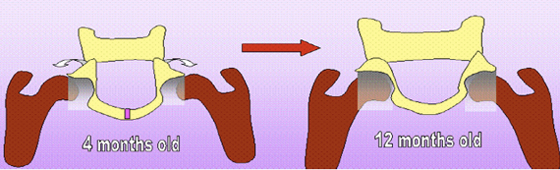

Juvenile pubic symphysiodesis (JPS)

This surgery involves induced premature fusion of part of the pelvis, in order to alter growth such that location of the ball part of the ‘ball-and-socket’ hip joint is improved. This is a simple surgery that involves electrical cauterization of part of the pubis (on the underside of the pelvis). In order to be effective, dogs must be a maximum of 5 months of age and must have mild-to-moderate laxity confirmed using manipulative and radiographic tests. As most dogs do not develop clinical signs until they are at least 6 months old, JPS is usually a prophylactic surgery. All dogs treated by JPS must be neutered at the same time.

Triple pelvic osteotomy (TPO)

This surgery involves the surgical modification of the existing hip joint to improve capture of the ball by the existing socket. Three cuts are created in the bones around the cup and the free segment thus created is rotated to a point that allows optimal hip capture. The bone segments are fixed in their new position using a custom plate and screws. Healing of the bone takes approximately 4-6 weeks. TPO is only effective in dogs that have hip laxity and no secondary remodeling of the bones or subsequent osteoarthritis. Assessment for TPO requires a specific series of manipulative tests and radiographs to be performed by both experienced orthopedic surgeons and advanced diagnostic imagers. Suitable dogs are most often clinically immature and arthroscopic examination of the joint is recommended to check for cartilage damage before surgery is performed. Recently a technique has been developed whereby the pelvis may only need to be cut in two places, called a double pelvic osteotomy.

Total hip replacement (THR)

Total Hip Replacement is an advanced surgical procedure which involves cutting out the whole of the diseased hip joint. The “ball” is replaced with a metal implant, and the “socket” is replaced with a plastic and metal implant. The implants can be attached to the bone using bone cement, or may have a porous coating into which the bone can grow. Although most of the dogs treated with THR are larger dogs, surgery can also be performed in small dogs and cats. Although some patients will need the surgery performed on both hips, we would never operate both hips at the same time as this could increase the risk of possible complications. The success rate for THR is approximately 90-95%, and most dogs are more comfortable within a few days of surgery. Many patients will return to full levels of activity.

Femoral head and neck excision (FHNE)

This operation is a salvage procedure usually only considered in cases where THR cannot be performed (e.g. for financial reasons or due to variations in individual anatomy that could preclude THR). In this technique, the femoral head and neck (the “ball” part of the joint) are completely removed allowing a “false joint” to form. Pain is relieved by elimination of bony contact between the ball and the edge of the socket, but the resulting “false joint” is typically limited in its function, so clinical outcome may be unpredictable, particularly in larger dogs. Intensive physical therapy is mandatory after FHNE for your dog to maximize return of mobility function.